Python Refresher II: Advanced Python

Now that we have covered the foundations, it is time to get a little bit more advanced. In this lesson, we will cover some more advanced ways to use Python, including how to write and run scripts, and how to use built-in methods for strings and data structures. We will also cover how to use control flow structures like loops, functions, and conditional statements.

Advanced Python

Python interpreter is great, but why might we not want to write all our code in the interpreter? What happens every time you quit?

It gets erased!

Rather than having to start from scratch every time, we can write our code in a script and then run that script. This is also how we can share our code with others.

Writing and Running Scripts

Open your is310-coding-assignments folder in VS Code, and create a new folder python-scripting. This is where we will store all our scripts for this lesson. Inside the python-scripting folder, create a new file called first_script.py. You can do this in the terminal by typing:

For Mac:

touch first_script.py

For Windows PowerShell:

ni first_script.py

We’re going to copy our code from the interpreter into this file:

favorite_movies =[

{

"name": "The Matrix I",

"release_year": 1999,

"sequels": ["The Matrix II", "The Matrix III", "The Matrix IV"]

},

{

"name": "Star Wars IV",

"release_year": 1977,

"sequels": ["Star Wars V", "Star Wars VI", "Star Wars VII", "Star Wars VIII", "Star Wars IX"],

"prequels": ["Star Wars I", "Star Wars II", "Star Wars III"]

}

]

Now save this file. You can do this by clicking File and then Save or by using the keyboard shortcut Cmd + S or Ctrl + S. Our next step is to run this script.

In our terminal, we can run the script by typing (but make sure you aren’t in the Python interpreter):

python3 first_script.py

What happens?

Because we aren’t in the interpreter any more, unless we tell the computer to output a value it won’t show us anything (unless there’s an error).

One solution is the print method.

In first_script.py, add the line to the bottom of the script:

print(favorite_movies)

This time you should see the list of movies printed out in the terminal when you run the script.

So what’s the print statement?

Built-In Methods

Print is a built-in Python method, which means it comes installed with Python and we can use it whenever we are writing Python.

Print is used to display (or print out) variables, values, and data to the terminal, which is useful for seeing what our code is doing. It’s also useful for debugging, which is the process of finding and fixing errors in our code.

Print is just one of many built-in methods though. Let’s take a look at a few more.

Len()Infirst_script.py, after our existing code, add the following:

total_favorite_movies = len(favorite movies)

print("How many total favorite movies do we have?", total_favorite_movies)

Then try saving your file and running the code in the terminal. You should see first our favorite movies, and then the total number of favorite movies printed out. While this example might seem trivial since we can easily count the number of items in our list, imagine we had hundreds or thousands of items in our list. This is where the len method comes in handy.

The len method can return the length of any list, dictionary, or string in Python.

Type()

So far we’ve been writing all our variables, but sometimes you will be working with code that you didn’t write. When that happens you might want to know what type of variable you are working with, which is where the type method comes in.

In first_script.py, add to the bottom of the script:

print(type(favorite_movies), type(favorite_movies[0]))

Once you save and run the script you should see that we have both a list and a dictionary. With print statements you can add multiple items as long as they are separated by commas, and you can use built-in methods inside the print statement, instead of assigning them to a variable first.

Input()

Now we have been writing all our data in our script, but what if we wanted to get input from the user? This is where the input method comes in.

In first_script.py, type the following at the bottom of the script:

print('Enter your favorite movie of the last year:')

recent_favorite_movie = input()

print('Your favorite movie is of the last year:', recent_favorite_movie)

What did we just do?

First we printed out a prompt (i.e. we used the print() method to display some text to our user). Then we assigned the input method to a variable called recent_favorite_methods, and then we printed out the value of that variable, along with some explanatory text.

You’ve now used built-in methods before for both dictionaries and lists. But they exist for data types too.

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

print() |

Prints out a value to the terminal | print('Hello World') |

len() |

Returns the length of a list, dictionary, or string | len([1,2,3,4,5]) |

type() |

Returns the type of a variable | type('Hello World') |

input() |

Gets input from the user | input('What is your name?') |

For more information about built-in methods, check out the Python documentation.

Built-In Methods for Strings

Now that we have mastered more complex data structures, we can start manipulating our data. With cultural data, we are often working text which in Python is represented as a string. Strings are a sequence of characters, and Python has many built-in methods for manipulating strings.

Split()

The split method lets us split up a string and turn it into a list. In first_script.py, add the following description of the movie The Matrix:

favorite_movies[0]['long_description'] = "The Matrix is a 1999 science fiction action film written and directed by the Wachowskis. It is the first installment in The Matrix film series, starring Keanu Reeves, Laurence Fishburne, Carrie-Anne Moss, Hugo Weaving, and Joe Pantoliano. The Waschowskis created a plot set in a dystopian future where humanity is unknowingly trapped inside a simulated reality, the Matrix, created by intelligent machines to distract humans while using their bodies as an energy source. In the movie, the main character, Neo, is a computer programmer who learns this truth and is drawn into a rebellion against the machines, which involves other people who have been freed from the Matrix."

print(favorite_movies[0])

When we save and rerun our code, we should now see this long_description printed out. As a reminder, to create long_description we are using indexing of our list and then adding a new key to the dictionary called long_description. We are then assigning a string to that key.

But what if we wanted to get a list of all the words in the description? We can use the split method to do this.

split_description = favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].split(' ')

print(split_description)

The split method takes a string and splits it up into a list of substrings. In this case, we are splitting the description of the movie The Matrix into a list of words. We are using the space character as the delimiter, which means that every time there is a space in the string, it will split the string into a new item in the list. You can use any character as a delimiter, and you can also use multiple characters as a delimiter.

Now that we have this split list, we could use len to count the number of words in the description:

print(len(split_description))

We could also decide that we want to create a shorter description key in our dictionary and use indexing range to get the first 10 words of the description:

favorite_movies[0]['short_description'] = ' '.join(split_description[:10])

print(favorite_movies[0]['short_description'])

Join()

You’ll notice that we use a new method in the example above called join. This method lets us take a list and join all the values together.

print(' '.join(split_description))

Like split(), join requires a delimiter, which in this case is a space. This means that every item in the list will be joined together with a space in between. You can use any character as a delimiter, and often you’ll see people use a comma to join lists together into a string.

Replace()

Now currently our description names the directors as the Wachowskis. But what if we wanted to change that to Lana and Lilly Wachowski? We can use the replace method to do this.

edited_description = favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].replace('the Wachowskis', 'Lana and Lilly Wachowski')

print(edited_description)

The replace method lets us find a string and replace it with another string. You can also specify how many times you want to replace a string. For example, if you only wanted to replace the first instance of the Wachowskis you could use the following:

edited_description = favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].replace('the Wachowskis', 'Lana and Lilly Wachowski', 1)

print(edited_description)

Lower(),Upper(),Title(),Strip()

Some additional methods that can be helpful include lower, upper, title, and strip. These methods let you change the case of a string, remove white space from the beginning and end of a string, and capitalize the first letter of each word in a string.

print(favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].lower())

print(favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].upper())

print(favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].title())

print(favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].strip())

| Method | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

split('delim') |

Returns a list of substrings separated by the given delimiter | split_description = favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].split(' ') |

join(list) |

Opposite of split(), joins the elements in the given list together using the string | ' '.join(split_description) |

replace('old string', 'new string') |

Replaces old string with new string | favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].replace('the Wachowskis', 'Lana and Lilly Wachowski') |

lower() |

Makes the string lowercase | favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].lower() |

upper() |

Makes the string uppercase | favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].upper() |

title() |

Makes the string titlecase | favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].title() |

strip() |

Removes lead and trailing white spaces | favorite_movies[0]['long_description'].strip() |

You can find more information about string methods here https://www.w3schools.com/python/python_ref_string.asp

Quick Exercise For Practice (Optional But Recommended)

- Create two variables in your script, one for your favorite movie and one for your favorite book. You can use any data structure you want.

- The variables should include the title, the year it was released, and any sequels or prequels or series.

- The script should then ask for input from the user for a description of their favorite movie and book. These should be assigned to new keys in the dictionary.

- The script should print out the length of the list of your favorite movies and books, should create a short description of your favorite movie and book, and should print out the length of the long description of your favorite movie and book.

Control Flow

So far we have been writing code that runs from top to bottom, but what if we moved our latest print statement to the top of our script? What would happen?

print(favorite_movies)

favorite_movies =[

{

"name": "The Matrix I",

"release_year": 1999,

"sequels": ["The Matrix II", "The Matrix III", "The Matrix IV"]

},

{

"name": "Star Wars IV",

"release_year": 1977,

"sequels": ["Star Wars V", "Star Wars VI", "Star Wars VII", "Star Wars VIII", "Star Wars IX"],

"prequels": ["Star Wars I", "Star Wars II", "Star Wars III"]

}

]

We’ve hit a problem. Let’s break down what happened here. If the print statement was at the bottom of the script it worked, but if it was at the top it didn’t.

That’s because the print statement within it’s parentheses references the variable favorite_movies, but we haven’t defined that variable yet. This is an example of a NameError. But it’s also helping us understand that Python reads code from top to bottom, line by line. This is called sequential execution and we can manipulate this with control flow structures.

Understanding control flow structures is essential to writing more complex code. These structures let us control the flow of our code, and they include loops, functions, and conditional statements.

Looping

So far, we have been working with a list of dictionaries and writing out individual print statements for each value. But this gets tedious quickly, especially as we add more values (imagine if we had hundreds or thousands of movies, for example).

There’s a much faster way to traverse data structures and types in Python, called Looping. With various types of loops in Python, you can travel through a sequence (i.e. a list, dictionary, string, etc…) to be able to manipulate items within the sequence.

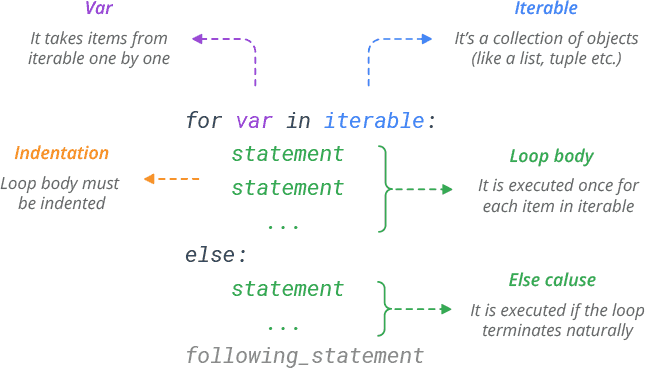

For Loops are one of the most common ways in python to loop over a sequence. But what does looping mean exactly?

Let’s take our list of favorite movies and print out the name of each movie.

for movie in favorite_movies:

print(movie['name'])

This diagram helps us understand this new syntax. We start with the for keyword (which is another reserved word in Python), followed by a variable name (in this case movie) and the in keyword (reserved word again), followed by the sequence we want to loop over (in this case favorite_movies). We then end the line with a colon, and indent the code we want to run for each item in the sequence.

Indenting is very important in Python. It tells Python that the indented code is part of the loop. If we don’t indent, Python will throw an error. To indent in Python, we use either two or four spaces (or tabs). You can use any number of spaces or tabs, but they have to be consistent. This use of white space is called indentation and is a core part of Python’s syntax.

Within the loop, we can use the variable movie to access each item in the sequence. This is called iteration. In this code, we are using the print statement to print out the name of each movie.

While we named our variable movie, we could have named it anything. For example, we could have named it film or item. The name of the variable is up to you, but ideally it should be descriptive of the items in the sequence.

Now what would happen if we tried to print movie outside of the loop?

for movie in favorite_movies:

print(movie['name'])

print(movie)

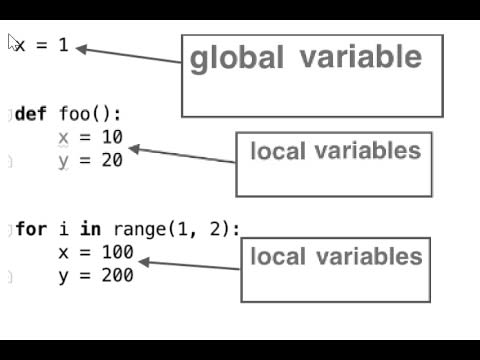

We would either get an error or the last movie in the list. This is because the variable movie only exists within the local scope of the loop. This is called local scope. This is also why we can use the same variable name in different loops and not have to worry about them conflicting with each other. We’ll go into detail about this more later in this lesson.

We can also use For Loops on dictionaries. The syntax is slightly different because dictionaries are not one long sequence, but rather a sequence of key/value pairs. Let’s try and loop through all the keys in our favorite movies.

individual_movie = favorite_movies[0]

for key, value in individual_movie.items():

print(key, value)

You’ll notice that we are using the items method to get the key/value pairs of the dictionary. This is a built-in method for dictionaries. We are then using the for keyword, followed by two variables (in this case key and value), and the in keyword, followed by the sequence we want to loop over (in this case individual_movie.items()). We then end the line with a colon, and indent the code we want to run for each item in the sequence. We can then use the key and value variables to access each item in the sequence. Instead of key and value, we could’ve used any name we wanted, like metadata and data.

Finally we can even loop through a string. Let’s try and print out each letter in the first name of our favorite movie.

first_movie_name = favorite_movies[0]['name']

for letter in first_movie_name:

print(letter)

Looping is fairly complex, but the core thing to remember is the reserved words for and in, and the colon at the end of the line. We then indent the code we want to run for each item in the sequence.

For more about looping in Python, check out the Python documentation and the W3Schools tutorial.

| Looping keyword | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

for |

Used to loop over a sequence | for movie in favorite_movies: |

in |

Used to specify the sequence to loop over | for movie in favorite_movies: |

items() |

Used to get the key/value pairs of a dictionary | for key, value in individual_movie.items(): |

Functions

Looping is very powerful, but if we want to loop through a second list of movies or a different variable, we would have to repeat our code later in the script. An alternative is to create a function.

A function is a way to organize code into a reusable block. It’s a way to avoid repeating code, and also to make our code more readable. Functions are also a way to make our code more modular and easier to fix.

Function Syntax

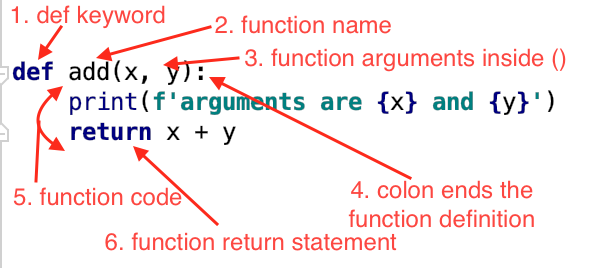

To create a function, we use the reserved word def and then create a unique name for our function, followed by parentheses and colon. Similar to variables, function names can contain letters, numbers, and underscores, but they cannot start with a number. We usually write function names in lowercase and use underscores to separate words.

Then we can pass arguments (also called parameters) in the parentheses, that we can that use inside of the functions. Those arguments will be variables and we can do any transformation you would normally do to a value. Finally we can return the result of our manipulation.

For example let’s create a function that takes a movie and prints out the name of the movie.

def print_movie_name(movie):

print(movie['name'])

print_movie_name(favorite_movies[0])

This function takes a movie as an argument and then prints out the name of the movie. We can then call this function and pass in a movie as an argument. This is called calling the function.

Now we could do a more complex function that takes a movie and a year and returns a string with the name of the movie and the year.

def print_movie_name_and_year(movie):

movie_data = movie['name'] + ' was released in ' + str(movie['release_year'])

print(movie_data)

print_movie_name_and_year(favorite_movies[0], favorite_movies[0]['release_year'])

You’ll notice in this example that we are using the + operator to concatenate the strings together. We are also using the str method to convert the integer to a string. This is because you can’t concatenate a string and an integer together. This type of transformation is called type casting, which is when we change the type of a variable. Finally we are assigning the result of our manipulation to a new variable called movie_data and printing that out.

What would happen if you try to access the variable movie_data outside of the function?

def print_movie_name_and_year(movie):

movie_data = movie['name'] + ' was released in ' + str(movie['release_year'])

print(movie_data)

print_movie_name_and_year(favorite_movies[0])

print(movie_data)

NameError: name 'movie_data' is not defined

Similar to our looping example, the variable movie_data only exists within the local scope of the function. In functions, everything indented within the function is part of the local scope. This is also why we can use the same variable name in different functions and not have to worry about them conflicting with each other.

In this diagram, we can start to see how where we define our variables impacts whether it is global or local scope. This is a core concept in Python and is called variable scope. So our favorite movies list is in the global scope, but the variable movie and movie_data are in the local scope of the function. Knowing the scope of your variables is essential because if you try to access something globally but it only exists locally, you’ll get an error. Alternatively, if you want to only change a variable locally but it exists globally, you’ll also end up overwriting the global variable. This is all very complex, but I promise with practice and time it will start to make sense.

The final part of a function is the return statement. This is used to pass data back from the function, which can then be assigned to a new variable that’s accessible in the rest of the script, also known as the global scope.

def print_movie_name_and_year(movie):

movie_data = movie['name'] + ' was released in ' + str(movie['release_year'])

return movie_data

new_movie_data = print_movie_name_and_year(favorite_movies[0])

print(new_movie_data)

Now we can see that we are assigning the result of our manipulation to a new variable called new_movie_data. This variable is accessible in the rest of the script, also known as the global scope.

For more about functions in Python, check out the Python documentation and the W3Schools tutorial.

| Function keyword | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

def |

Used to define a function | def print_movie_name(movie): |

return |

Used to pass data back from the function | return movie_data |

Conditional Statements

So far we have been manipulating all our code the same way, but what if we wanted to have a different manipulation for different types of movies? Or for movies versus books? This is where conditional statements come in.

Earlier we learned about booleans (True or False). So we could test if our two movies are the same.

print(favorite_movies[0] == favorite_movies[1])

This should output False, but we can also use this type of condition to perform different actions with our code.

if favorite_movies[0] == favorite_movies[1]:

print('The same')

else:

print('Different')

In this example, we are doing the same comparison as before, but now we are using the if keyword, followed by the condition we want to test, followed by a colon. We then indent the code we want to run if the condition is True. We can also use the else keyword to run code if the condition is False. This is called an if/else statement. Both if and else are reserved words in Python. And with these keywords, we can create complex logic in our code.

We can also use the elif keyword to add more complexity to our code. Each of the conditional blocks (the three print() statements) are only run if the associated conditional statement is True (in the boolean logic sense). We can have multiple elif blocks if we want. We can also omit elif and else blocks altogether.

if favorite_movies[0] == favorite_movies[1]:

print('The same')

elif favorite_movies[0] != favorite_movies[1]:

print('Different')

else:

print('No idea')

In this example, if our initial condition is True, we print out The same. If it’s False, we then test the next condition with the elif (which stands for else if). If that’s True, we print out Different. Finally, if that is also False, we print out No idea.

In conditional statements, we can use any of the previous operators we’ve learned about, including ==, !=, >, >=, <, and <=. We can also test more complicated comparisons using various comparison operators:

For strings, we can use use == for comparison and some special operators like in to see if one string exists inside of another.

if 'Matrix' in favorite_movies[0]['name']:

print('Matrix')

else:

print('No Matrix')

We can also use == to test numbers:

if favorite_movies[0]['release_year'] == 1999:

print('The Matrix')

else:

print('Not The Matrix')

For numbers, we can also use >, >=, ==, <, and <= to make numeric comparisons.

if favorite_movies[0]['release_year'] > favorite_movies[1]['release_year']:

print('The Matrix')

else:

print('Star Wars')

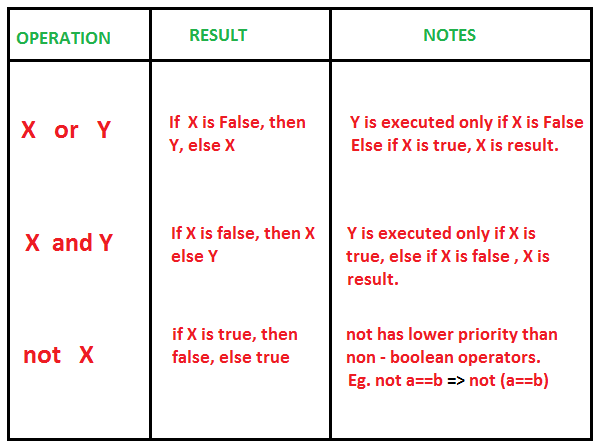

We can also do more than one condition, we can use and, or, and not:

if favorite_movies[0]['release_year'] > 1999 and 'Matrix' in favorite_movies[0]['name']:

print('The Matrix')

else:

print('Star Wars')

if not favorite_movies[0]['release_year'] > 1999:

print('The Matrix')

else:

print('Star Wars')

Finally we can also check if a variable exists or not using is and is not:

if favorite_movies[0]['sequels'] is not None:

print('Sequels')

else:

print('No Sequels')

You’ll notice we’re using a new keyword None. This is a special Python object that represents the absence of a value. It’s similar to null in other programming languages. We can use is and is not to check if a variable is None or not.

For more about conditional statements in Python, check out the Python documentation and the W3Schools tutorial.

| Conditional keyword | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

if |

Used to test a condition | if favorite_movies[0] == favorite_movies[1]: |

elif |

Used to test another condition | elif favorite_movies[0] != favorite_movies[1]: |

else |

Used to run code if the condition is False | else: |

in |

Used to test if a string exists in another string | if 'Matrix' in favorite_movies[0]['name']: |

and |

Used to test if two conditions are True | if favorite_movies[0]['release_year'] > 1999 and 'Matrix' in favorite_movies[0]['name']: |

or |

Used to test if one of two conditions is True | if favorite_movies[0]['release_year'] > 1999 or 'Matrix' in favorite_movies[0]['name']: |

not |

Used to test if a condition is False | if not favorite_movies[0]['release_year'] > 1999: |

is |

Used to test if a variable is None | if favorite_movies[0]['sequels'] is not None: |

is not |

Used to test if a variable is not None | if favorite_movies[0]['sequels'] is not None: |

None |

A special Python object that represents the absence of a value | None |

Homework: Scripting Python Foundations (Optional But Recommended)

This homework assignment is optional but highly recommended for those that do not have experience with writing Python scripts. If you decide to complete the homework, it will be added to your grade as extra credit but if you do not complete it, it will not be counted against you.

In the first quick exercise, you created a script that asked for input from the user and then printed out the length of the list of your favorite movies and books, created a short description of your favorite movie and book, and printed out the length of the long description of your favorite movie and book.

Now we will augment this script to include loops, functions, and conditional statements.

In your first_script.py, try to complete the following tasks:

- Create a function that takes a movie as an argument. Inside the function, it should check if the movie was released before 2000. If it was, it should print a string that says “This movie was released before 2000”. If it wasn’t, it should print a string that says “This movie was released after 2000”. The function should only return the movie name if it was released after 2000.

- Below the function create an empty list called

recent_movies. - Outside and below the function and

recent_movies, use a for loop to loop through all the movies in your list of favorite movies. For each movie, call the function and pass in the movie as an argument. If the function returns a value, append the movie to therecent_movieslist. You can check if the function returns a value by using theifkeyword and checking if the result isNoneor not. - Finally, outside of the loop, print out the

recent_movieslist.

Once you have completed this script, save it and run it in the terminal. You should see a list of all the movies that were released after 2000. If you prefer, you can use books or another cultural object instead of movies.

After confirming that the script works, you should push it up to your GitHub repository. You can do this by using the following commands in the terminal:

git add .

git commit -m "Completed homework for Python Foundations"

git push origin main # or master if you haven't changed the default branch name

You should then put a link to our GitHub discussion https://github.com/CultureAsData-UIUC/is310-fall-2024/discussions/7.